Famine

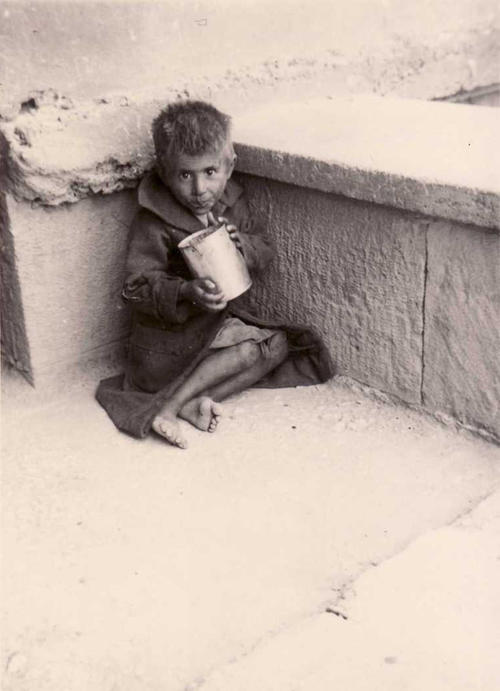

Starving child in Athens, 1942. Private collection George Chandrinos

Starving Athenians looking for food in garbage bins. Private collection Iassonas Chandrinos

I received a lamentable report on the situation in Greece. The hunger there has become a national epidemic. Thousands of people are dying on the streets of Athens, all a result of the brutal British blockade against a people who wanted to carelessly pick out of the fire the chestnuts for the English people. That's the gratitude of London.

Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda of the Third Reich

“The problem is: Is the good will of the Greeks worth? Weighing its fleet, the effectiveness of their passive resistance and armed resistance is more difficult for us if we facilitate the grain supply for Greece. Is it important for us to maintain a healthy population of 7 ½ million anglophile Greeks in order to underpin our postwar position in the eastern Mediterranean? Or can we allow that Greece's population will be reduced to five million because of hunger and allow ruin their health - especially the children - and ruin also their attitude that will become violently anti-British? The pros and cons must be carefully weighed against each other before we commit ourselves to starve Greece. We have to consider also that Greeks will not starve in silence. In addition, we have to consider the impact on public opinion in the United States.”

Edward Warner, F.Ο. Report, July 11th, 1941.

Greece experienced widespread and longterm starvation during the occupation. The most serious adverse effect of the Occupation of Greece was hunger. The scarcity of food had already appeared in the first days of the German invasion and this was a disturbing fact for the whole population. Hunger had more victims than bombings, guerrilla warfare and even reprisals, and is deeply engraved in the Greek collective memory. The most terrible period was the first winter of 1941–1942, where no less than 30,000 people died, the largest part of those in urban areas. The famines in Greece and Holland were the most lethal in occupied Europe during the Second World War. It is estimated that the Greek famine killed close to 5 percent of the population. The people in urban centers suffered more than those who lived in the countryside. According to the records of the German army, the mortality rate in Athens reached 300 deaths per day during December 1941.

Even immediately after the conquest of the country, the food crisis was out of control and thousands of people died as consequence. Due to the propagandistic exploitation of the famine and the terrible losses, the Germans were accused of an attempted genocide. They allegedly implemented a strategic plan to starve the Greeks. Tens and thousands of people had to flee to other parts of the country, driven by the war and the confusion triggered from the conquest and partition of the country into zones of occupation. Since the majority had moved in search of a better life, this uncontrolled flow of people quickly led to a glaring imbalance between the flooded urban areas and the rural areas, where most families relatively easily maintained their standard of living. Of course, if the country would not have been occupied, the food supply would not have been affected so catastrophically.

The collapse of the transport links to the whole country had caused considerable difficulties to deliveries from one area to the other. Large stocks of potatoes, raisins, olive oil and other resources that were considered surplus products were intended for export to the German Reich. Greece could not expect imports for the duration of the war. On September 6th, 1941, the rationing of food for the inhabitants of the capital was fixed by law. At the same time, the black market had assumed enormous dimensions. According to contemporary sources, most of the crop was not delivered to the public but moved to speculators and middlemen in smuggling. The illegal market has been extended to all areas of the everyday economy. Within a few months, food stores, shops and markets gradually disappeared. Soup kitchens were organized by the church and the Red Cross, but the success was inconsistent and hopelessly inadequate.

Although people from all classes perished, we should not obscure the fact that the majority of victims came from the lower classes. The streets of Athens showed an appalling image. People collapsed in the street every day and passersby walked indifferently by while dying people were left lying on the road. The islands, which were agriculturally self-sufficient and where the mortality rate was higher than in the poorest neighborhoods of Piraeus, were among the areas that were also severely affected. The number of dead is beyond the reach of documented statistics and is thus very difficult to calculate.